Our Life Priorities Are Wrong

We’re forgetting the value of boredom

21 min read

Photo by Mike Erskine on Unsplash

I was sitting on the porch, swinging my little legs. I grabbed a pinch of sand and slowly raised my hand while easing the grip and letting the sand slide through my fingers. I noticed how it dissipated and how the sunlight ran through it and lit it with gold particles.

I was about 9, spending my summer vacation at my grandparents in the village of Negureni. I didn’t know what Internet was, I didn’t know who our President was, and I didn’t know “the top 10 tips of how to be more productive”. For all I cared, I spent my time outside with other kids, running barefoot and playing cops with sticks instead of guns. I stole green apricots from neighbor’s backyard because I was too impatient to let it ripen properly. I still remember that bitter taste in my mouth and how I’d squint every time and still eat it regardless. I’d play football till the Sun came down and my grandma would yell like an angry Luciano Pavarotti half a kilometer away “Andriesh! Dinner is ready, move your ass back home!”.

And sometimes, when other kids were busy, I’d just sit and look at the trees. Have you noticed how they move when the wind blows? How their branches move gently back and forth? Like a dance. And the sound. Oh, the sound. That ruffling and shuffling of leaves. I love the feeling you get right before a summer storm, when the clouds get darker and darker, and the wind gets wilder, and you have this giddy feeling in your stomach like you want to get inside the house and feel cozy, but you still stay outside and observe, like the curious monkey that you are, feeling awe and fascination from this thing called nature and how alive it can be when you’re close to it.

I don’t remember the last time I felt that. But I remember what person X posted last on her Facebook profile. I don’t remember the smell of the storm, but I remember how anxious I felt when I was checking the likes on one of my posts.

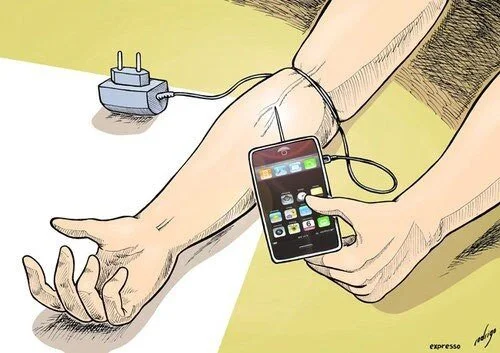

I don’t remember the last time I was genuinely bored. Like, I mean, really bored. With no phone in my pocket with infinite amount of entertainment that can distract me anytime I want. Yes, I realize that at least I’m self-aware enough to notice when I overdo it so I try to limit my social media and tech consumption. I’d like to think I’m good at that. But I can’t help but notice that this threshold of what is normal changes with every few years. It used to be about 10 years ago that you’d still see people not looking down their phone when they have to wait in line or have dinner at the restaurant. They’d have their heads up and their eyes scanning the environment, trying to spark a conversation because they were bored or they felt awkward towards the person sitting across. Now it’s more widely acceptable to see couples checking their Instagram when they have dinner or get their daily dopamine from the infinite Facebook feed.

Again, that’s my observation, maybe I romanticize the past, I don’t know. But I do feel there’s some truth to that. I do feel we’re losing something. I do feel that I was part of the last generation that had a childhood without iPads and infinite entertainment at our fingertips. I had more space in my head to wonder, to think about unimportant stuff, to be a kid.

We’re forgetting the value of boredom, and it’s making us depressed

That sounds like a trivial issue, but I beg to differ. I think it’s an important one, and if we stop appreciating it we’re going to see depression in teenage kids only increase in the next few years. There’s multiple studies that confirm this trend. Most of them say that teen depression and social media go hand-in-hand, meaning that the consumption of social media has the potential to make teens more depressed, and the pressure to fit into the crowd amplifies while their social skills decrease.

“Research shows an increase in major depressive episodes from 8.7% in 2005 to 11.3% in 2014 in adolescents and from 8.8% to 9.6% in young adults. The increase was larger and only statistically significant only in the age range of 12 to 20 years. Clearly depression is on the rise among teens, the question we need to ask ourselves is how much does technology and social media contribute to it?

It’s no big secret that connecting via texting, Instagram, and Facebook can include harsh judgments and comparisons. It’s easier to make statements on a screen that would otherwise be difficult to verbalize face to face. And disjointed shorthand conversations can easily result in misunderstandings. It doesn’t help that digital communication occurs at a rapid pace, one that is difficult to process at times.

One report by the Royal Society for Public Health in the UK surveyed 1500 young people, ages 14 to 24, to determine the effects of social media use on issues such as anxiety, depression, self-esteem, and body image. Their findings show that YouTube had the most positive impact, while Instagram, Facebook, Twitter, and SnapChat all had negative effects on mental health.”

Also, curiously, teenage girls are more affected by it than boys, as this report confirms:

Among teens who use social media the most — more than five hours a day — the study showed a 50% increase in depressive symptoms among girls versus 35% among boys, when their symptoms were compared with those who use social media for only one to three hours daily.

“We were quite surprised when we saw the figures and we saw those raw percentages: the fact that the magnitude of association was so much larger for girls than for boys”, Kelly said.

The researchers also found that girls reported more social media use than boys; 43.1% of girls said they used social media for three or more hours per day, versus 21.9% of boys.

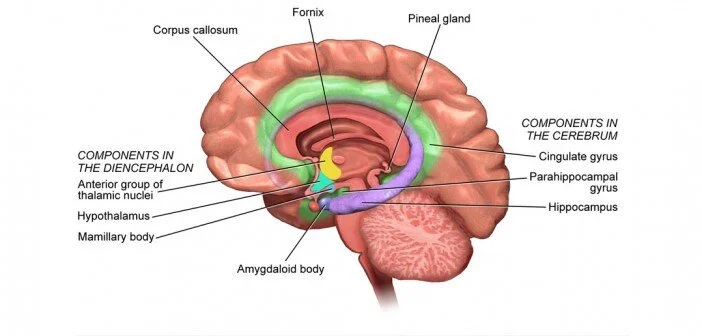

The reason why girls are more negatively affected by social media than boys may be explained by this brain imaging study, which shows that “women experience negative emotions differently than men”:

“Not everyone’s equal when it comes to mental illness,” said Adrianna Mendrek, a researcher at the Institut universitaire en santé mentale de Montréal and lead author of the study. “Greater emotional reactivity in women may explain many things, such as their being twice as likely to suffer from depression and anxiety disorders compared to men,” Mendrek added, who is also an associate professor at the University of Montreal’s Department of Psychiatry.

In their research, Mendrek and her colleagues observed that certain areas of the brains of women and men, especially those of the limbic system, react differently when exposed to negative images. They therefore investigated whether women’s brains work differently than men’s and whether this difference is modulated by psychological (male or female traits) or endocrinological (hormonal variations) factors.

For the study, 46 healthy participants — including 25 women — viewed images and said whether these evoked positive, negative, or neutral emotions. At the same time, their brain activity was measured by brain imaging. Blood samples were taken beforehand to determine hormonal levels (e.g., estrogen, testosterone) in each participant.

The researchers found that subjective ratings of negative images were higher in women compared to men. Higher testosterone levels were linked to lower sensitivity, while higher feminine traits (regardless of sex of tested participants) were linked to higher sensitivity. Furthermore, while, the dorsomedial prefrontal cortex (dmPFC) and amygdala of the right hemisphere were activated in both men and women at the time of viewing, the connection between the amygdale and dmPFC was stronger in men than in women, and the more these two areas interacted, the less sensitivity to the images was reported. “This last point is the most significant observation and the most original of our study,” said Stéphane Potvin, a researcher at the Institut universitaire en santé mentale and co-author of the study.

The amygdale is a region of the brain known to act as a threat detector and activates when an individual is exposed to images of fear or sadness, while the dmPFC is involved in cognitive processes (e.g., perception, emotions, reasoning) associated with social interactions. “A stronger connection between these areas in men suggests they have a more analytical than emotional approach when dealing with negative emotions,” added Potvin, who is also an associate professor at the University of Montreal’s Department of Psychiatry. “It is possible that women tend to focus more on the feelings generated by these stimuli, while men remain somewhat ‘passive’ toward negative emotions, trying to analyse the stimuli and their impact.”

But it’s not all doom and gloom. Some recent studies say that teens that are already depressed tend to use social media more — a sort of who came first: chicken or the egg kind of question. It’s not entirely clear, maybe depressed people tend to use social media more as a crutch to make themselves feel better, and ironically, because of how it is built, it only tends to aggravate that depression even more. Here’s what this study says:

Time spent on Instagram, Snapchat or Facebook probably isn’t driving teenagers to depression, a new study contends. The new study looked at people over time and tried to make sense of their behaviors over time, said Rutledge, who was not involved in the research.

“To me it makes a lot of sense, because we also know that social media can have a lot of benefits,” she said. “With anything, there is positive and negative. Social media is this great big thing, and there are all sorts of ways to use it.”

Beginning in 2017, researchers led by Taylor Heffer from Brock University in St. Catharines, Ontario, surveyed nearly 600 sixth-, seventh- and eighth-graders in Ontario once a year for two years. They also conducted annual surveys of more than 1,100 college students for six years, beginning in 2010.

Social media use did not predict the development of depression symptoms among school kids or college students, researchers found.

Instead, school-age girls with greater symptoms of depression tended to use more social media over time. The researchers did not find the same association among school-age boys or college students.

“It’s definitely more sophisticated than the prior reports,” said John Piacentini, director of the UCLA Center for Child Anxiety Resilience Education and Support. “I believe it. I think it’s a nice contribution, and it clarifies this question in an important way.”

Rutledge said it could be that girls suffering depression might find solace in Snapchat or Instagram.

“If their offline life is unpleasant, they’re feeling marginalized at school, when you go online and you’re in one of these communities it feels good, because you’re now a valued member of something,” she said. “Maybe they use social media more to connect with people, and if they didn’t, maybe they’d be more isolated.”It makes sense that children would use social media differently based on their individual characteristics, said Dr. Paul Weigle, a child and adolescent psychiatrist in Mansfield Center, Conn.

“We need to take a closer look at groups and what makes young people different in their experiences with social media,” he said. For example, teens dealing with depression or anxiety might prefer socializing online because it’s easier to control interactions.

“They can stop and think before they respond,” Weigle said. “They don’t have to worry about changes in their voice or how they appear while they are responding.”

Moderation is important, as it is in all things, he added.

“It can lead to a pattern of avoiding,” Weigle said. “Some depressed youth use social media and other types of screen media as an escape from their real-world problems. When they avoid their real-world problems, these problems tend to grow rather than shrink.”

Our biology is not (yet) adjusted to our high-tech environment

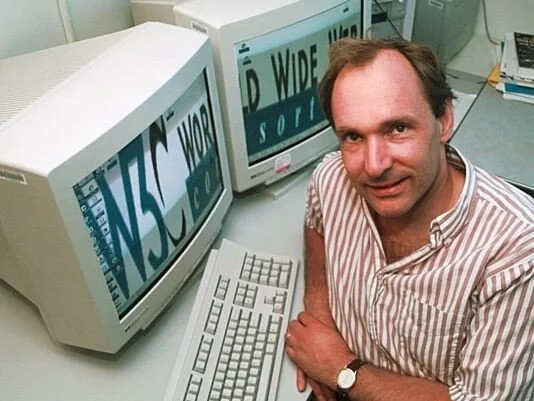

We’ve only had internet for 30 years. It has literally changed the way our world operates and we’re yet to fully grasp its effects on our human species as a whole.

Tim Berners-Lee invented the World Wide Web in 1990.

30 years is nothing, it’s not even half of the average life span of a human being. There’s no way our biology can adjust so fast and adapt to this new environment. That takes tens — if not — hundreds of thousands of years. Evolution is very VERY slow.

We may seem like we’re already adapted to this invasion of high-tech in our lives, but don’t be fooled, we’re not. We’re doing our best we can with what we have, but we’re just at the beginning of this new era, the era in which technology is surpassing the limits of our human biology. That’s good and bad at the same time. I tend to be more positive about it. I think that overall new technology will bring (and is already bringing) good to our world, like fully-functioning artificial body organs, self-driving cars that statistically reduce the rate of accidents and deaths, better medicine and antibiotics, and hopefully sometime in the future the cure for cancer.

All that wouldn’t be possible without breakthroughs in technology and that always brings the initial skepticism and the more negative view of “the new”, like television did in the 1940’s or airplanes did in the beginning of 20th century. All that skepticism is healthy, because although I’m more positive than negative about our future, I think it’s foolish to ignore the danger it brings, and it always does. We have to be aware of it, and we have to learn to navigate in this new environment.

Just recently, Tim Berners-Lee, the inventor of the World Wide Web, has declared that “The web is now dysfunctional with perverse incentives.” Now if that doesn’t ring the alarm bell, I don’t know what will.

We underestimate the dangers of social media

One of the more pessimistic people about social media is the pioneer of virtual reality, Jaron Lanier. He has books like “10 Arguments For Deleting Your Social Media Accounts Now” or TED talks like “How We Need To Remake The Internet”. In that talk he mentions a quote from a book from the 1950’s called The Human Use of Human Beings by Norbert Wiener, which said:

One could imagine a global computer system where everybody has devices on them all the time, and the devices are giving them feedback based on what they did, and the whole population is subject to a degree of behavior modification. And such a society would be insane, could not survive, could not face its problems. But this is only a thought experiment, and such a future is technologically infeasible.

Lanier continued, “And yet, of course, it’s what we have created, and it’s what we must undo if we are to survive.”

Yes, this is a more pessimistic view of social media and the internet, and I don’t fully agree with it, but it has good arguments, and it’s stupid to just ignore it. I do believe — and I’m not the only one — that the way social media currently operates is a kind of sickness. It exploits our psychological vulnerabilities, without us being aware of it, and in the wrong hands that is very dangerous indeed. I don’t think we want to live in a world where every new technology is made to track and optimize itself based on human behavior. That may sound good, if you take money out of it, but the reality is — the way our capitalist society is set up — it’s competitive and it’s unforgiving. This is good because it promotes innovation and adaptability, but it’s bad because it encourages exploitative and ruthless behavior that would keep a company alive and prospering.

So we end up with two sides of the same coin:

On one side we have Netflix that is a payed service and is tracking our behavior, giving us relevant recommendations based on our viewing history.

On the other side we have Facebook that is a “free” service and is tracking our behavior, selling and leaking our information to private companies that use it to optimize their efficiency and market value.

I think it’s pretty obvious that we should be wary of how our data is used if we want to preserve some sense of agency over our choices and lifestyles. We need to stay skeptical.

We see human connection as an option rather than a necessity

You’re not a lone wolf. Stop thinking of yourself as one, even if you like solitude. (like I do)

Tribalism and the need to be part of a community is in our DNA. We feel shame because we sense the danger of being isolated from our tribe — which would lower our chances of survival in prehistoric times. We feel jealousy over our partner because we want to make sure they reproduce with us and the offspring is ours. We seek loyalty from our friends because we knew that harsh times would come when they would help us kill the mammoth in the harsh winter and help us survive.

Basically, we’re all programmed to be part of a tribe. We’re social creatures. One of the surprising discoveries of substance addiction has been that addiction is conditioned primarily because of social isolation and lack of human connection. In that lack an isolated person seeks connection with the drug and indulges in it. A good example is hospital patients that are drugged with morphine for weeks and then come back home to their friends and family with no itch to get more morphine. While those that were isolated from people in the first place, would still have that itch when they return to society. Yes, there are physical and genetic factors, and some people are more predisposed to addiction, but isolation is a far more deadlier weapon in this game.

In a TED talk, psychiatrist Robert Waldinger speaks about a 75-year-old study on adult development. The main lesson he learned from people of different backgrounds, rich and poor, was that the biggest and most predominant factor in human happiness is — surprise surprise! — human connection, our relationships with other people. And yet so many of us have our priorities in life totally backwards.

There was a recent survey of millennials asking them what their most important life goals were, and over 80 percent said that a major life goal for them was to get rich. And another 50 percent of those same young adults said that another major life goal was to become famous.

The Harvard Study of Adult Development may be the longest study of adult life that’s ever been done. For 75 years, we’ve tracked the lives of 724 men, year after year, asking about their work, their home lives, their health, and of course asking all along the way without knowing how their life stories were going to turn out.

Studies like this are exceedingly rare. Almost all projects of this kind fall apart within a decade because too many people drop out of the study, or funding for the research dries up, or the researchers get distracted, or they die, and nobody moves the ball further down the field. But through a combination of luck and the persistence of several generations of researchers, this study has survived. About 60 of our original 724 men are still alive, still participating in the study, most of them in their 90s. And we are now beginning to study the more than 2,000 children of these men. And I’m the fourth director of the study.

Since 1938, we’ve tracked the lives of two groups of men. The first group started in the study when they were sophomores at Harvard College. They all finished college during World War II, and then most went off to serve in the war. And the second group that we’ve followed was a group of boys from Boston’s poorest neighborhoods, boys who were chosen for the study specifically because they were from some of the most troubled and disadvantaged families in the Boston of the 1930s. Most lived in tenements, many without hot and cold running water.

When they entered the study, all of these teenagers were interviewed. They were given medical exams. We went to their homes and we interviewed their parents. And then these teenagers grew up into adults who entered all walks of life. They became factory workers and lawyers and bricklayers and doctors, one President of the United States. Some developed alcoholism. A few developed schizophrenia. Some climbed the social ladder from the bottom all the way to the very top, and some made that journey in the opposite direction.

To get the clearest picture of these lives, we don’t just send them questionnaires. We interview them in their living rooms. We get their medical records from their doctors. We draw their blood, we scan their brains, we talk to their children. We videotape them talking with their wives about their deepest concerns. And when, about a decade ago, we finally asked the wives if they would join us as members of the study, many of the women said, “You know, it’s about time.”

So what have we learned? What are the lessons that come from the tens of thousands of pages of information that we’ve generated on these lives? Well, the lessons aren’t about wealth or fame or working harder and harder. The clearest message that we get from this 75-year study is this: Good relationships keep us happier and healthier. Period.

We’ve learned three big lessons about relationships. The first is that social connections are really good for us, and that loneliness kills. It turns out that people who are more socially connected to family, to friends, to community, are happier, they’re physically healthier, and they live longer than people who are less well connected. And the experience of loneliness turns out to be toxic. People who are more isolated than they want to be from others find that they are less happy, their health declines earlier in midlife, their brain functioning declines sooner and they live shorter lives than people who are not lonely. And the sad fact is that at any given time, more than one in five Americans will report that they’re lonely.

And we know that you can be lonely in a crowd and you can be lonely in a marriage, so the second big lesson that we learned is that it’s not just the number of friends you have, and it’s not whether or not you’re in a committed relationship, but it’s the quality of your close relationships that matters. It turns out that living in the midst of conflict is really bad for our health. High-conflict marriages, for example, without much affection, turn out to be very bad for our health, perhaps worse than getting divorced. And living in the midst of good, warm relationships is protective.

And the third big lesson that we learned about relationships and our health is that good relationships don’t just protect our bodies, they protect our brains. It turns out that being in a securely attached relationship to another person in your 80s is protective, that the people who are in relationships where they really feel they can count on the other person in times of need, those people’s memories stay sharper longer. And the people in relationships where they feel they really can’t count on the other one, those are the people who experience earlier memory decline. And those good relationships, they don’t have to be smooth all the time. Some of our octogenarian couples could bicker with each other day in and day out, but as long as they felt that they could really count on the other when the going got tough, those arguments didn’t take a toll on their memories.

So this message, that good, close relationships are good for our health and well-being, this is wisdom that’s as old as the hills. Why is this so hard to get and so easy to ignore? Well, we’re human. What we’d really like is a quick fix, something we can get that’ll make our lives good and keep them that way. Relationships are messy and they’re complicated and the hard work of tending to family and friends, it’s not sexy or glamorous. It’s also lifelong. It never ends. The people in our 75-year study who were the happiest in retirement were the people who had actively worked to replace workmates with new playmates. Just like the millennials in that recent survey, many of our men when they were starting out as young adults really believed that fame and wealth and high achievement were what they needed to go after to have a good life. But over and over, over these 75 years, our study has shown that the people who fared the best were the people who leaned in to relationships, with family, with friends, with community.

If we want a healthy mind, we need to rethink our priorities

So let’s set this straight:

1) Human connection > Facebook likes

2) Leaving space for boredom > distracting ourselves with phones

3) Observing the nature > constantly checking the news

1.

Talk to people face-to-face, and pay attention, ask inviting questions, be curious about the world. And keep that phone away for a while, don’t worry, those Facebook notifications will still be there, you won’t miss anything.

Don’t be your phone’s b*tch, make the phone your own b*tch.

2.

You’re bored? Good, it means you’re still human and you’re not a robot (yet).

When I was a kid and would be bored to death I’d ask my mom “Maaaahm, I’m bored, what should I do?”, to which my mom would respond “grab your ass and jump”, and I would. To this day this is the funniest sh*t she’s ever said to me. Love you, mom.

Boredom is the birthplace of great ideas, inventions, and creativity. Our imagination and curiosity is arguably the most distinguishing thing we have from other species on this planet. And we wouldn’t have it if we weren’t bored sometimes. Imagine if Leonardo Da Vinci had an iPhone, damn, he wouldn’t get sh*t done. He’d be craving them likes and shares and he’d be sending picks of his crotch to them ladies.

Okay, I exaggerate for comedic value, but I think there’s some truth to it. If the pioneers of the Renaissance era had phones and social media they would be waaay to distracted to create the good stuff. Hmm, but then if Genghis Khan had porn on his phone then maybe he would’ve abstained from raping half of Europe and Asia? Maybe. (ekhm, we need more research on that)

So stop distracting yourself all the time, let your mind wander. Let it go places. Give it space. Be bored. Maybe something good will come out of it. Maybe not. It’s worth a try, trust me.

3.

A very cheerful lad, Henry David Thoreau, once said:

“The mass of men lead lives of quiet desperation. What is called resignation is confirmed desperation. From the desperate city you go into the desperate country, and have to console yourself with the bravery of minks and muskrats. A stereotyped but unconscious despair is concealed even under what are called the games and amusements of mankind. There is no play in them, for this comes after work. But it is a characteristic of wisdom not to do desperate things…

…you must live in the present, launch yourself on every wave, find your eternity in each moment. Fools stand on their island of opportunities and look toward another land. There is no other land; there is no other life but this.”

Source

This is the part I know I lack. Observing the nature, admiring it, and just simply being. I live in a big city and I work downtown. All I see is cars, subways, and concrete. I’ve read — and I’m sure you did too — many articles about how “being in nature even for 20 minutes a day regulates our mood and gives us the happy hormones”. It’s a cliché, but it’s true. It’s hard to argue against it, because when you do it, you feel it. It helps. I mean, the world we see now with skyscrapers and cars and glass and concrete is relatively new. It’s only been like that for about 200 years. And as I mentioned before, our biology is not fully adapted to it, we’re estranged by our own environment. Our ancestors lived, hunted, and had wild sex in nature among all the beautiful bugs and mosquitoes and hungry wolves. (ugh, how did they manage?) Want it or not, we still have that primitive part of the brain in all of us, so in order to keep it happy, we need to remember the basics. Nature, good food, relationships, and obviously Netflix. I mean come on, did you see the last season of True Detective? It’s great, but the first season is still the best, trust me.

Try this experiment: do you remember what you saw on your Facebook feed 2 days ago? Hard to remember? Yeah, me too. Why do we do it so much? Idk, because we want to be informed and up to date with current world affairs and the updated status of the “we met once in our lives but I’ll send you a friend request” kind of friends? Or maybe it’s because the Facebook feed is built exactly like the lottery machine in a casino which gives us dopamine hits and exploits our thirst for novelty? I don’t know, it’s really up to you to decide.

I know one thing: the monkey inside of us needs to look at trees sometimes, and it needs another monkey to talk with. So keep the monkey happy and watch the trees with somebody.